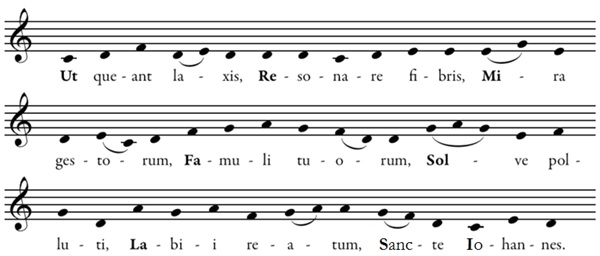

"Hymn to St. John the Baptist" in common western notation.

Ut - Re - Mi - Fa - Sol - La

Shape-note singing has been one of America's best-kept secrets. It can be found in many different traditions and customs.

The development of shape-notes has been a tremendous aid to help people learn to read music. While critics of shape-notes see them as little more than a crutch, the original purpose of the shape-notes was to quickly teach musically illiterate individuals to read music. This philosophy remains true today. Usually, the shape-note technique is taught at singing schools.

Let us look at how we got to where we are today.

The Development of Do Re Mi

The person who has the biggest impact on this system was an Italian Benedictine monk named Guido of Arezzo (c. 990-1050). He noticed that his fellow monks were having trouble remembering the tunes of their hymns and chants. His solution to assist the monks became the foundation of the music system we use today.

Guido noticed that there was a particular hymn in which the first note of each line progressed upward a degree step. From this he developed a six-note scale system. He took the first syllable of each line in this hymn to develop a system of solemnization for this scale.

In the late 1500s, a seventh syllable, or leading tone, was added to the scale. This new syllable was called "Si," named from the initials of the last two words, "Sancte Iohannes," of the original hymn. We do not know who came up with the idea of adding this syllable; some sources claim it was Puteanus of The Netherlands, while others claim it was Lemaire of France. The celebrated historian of that time, Mersennus, believed it was Lemaire.

Sometime in the 1600s, an Italian musicologist named Giovanni Battista Doni (c. 1593-1647) suggested changing "Ut" to "Do." It was his belief that "Ut" sounded too harsh and was less pleasing to the ear. This syllable came from the first syllable of Doni's name. Doni also suggested changing the seventh syllable to "Ni," after the second syllable of Doni's name, but this proposal was not successful.

The last change to this scale was made in 1835 by Sarah Ann Glover (1785-1867) of Norwich, England, when she published Scheme for Rendering Psalmody Congregational. In her new book she used the Tonic Sol-Fa method of music notation. For this new music notation, the seventh syllable was changed from "Si" to "Ti."

Rev. John Curwen (1816-1880) discovered Miss Glover's music notation and perfected her system to generate a teaching tool.

More on this later in The Tonic Sol-Fa Music Reader section.

The Change to Fa Sol La

In the late 1500s, a new scale system was developed in Geneva. This system abandoned the use of "Ut," "Re," and "Si." This scale uses "Fa," "Sol," and "La" twice, followed by "Mi" for the leading note, or seventh note of the scale. The use of this new system soon found its way to England.

Thomas Morley printed A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke in 1597. In this book, Morley teaches music using the Guidonian syllables while at the same time he shows substituting "Fa" for "Ut."

In 1668, Christopher Simpson wrote The Principles of Practical Musick. He said, "For this Cause, as also for Order and Distinction [sic.] sake, six Syllables were used in former Times, viz. Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, which being joined with these seven Letters, their Scale was set down in this manner, as follows:

"Four of these, to wit, Mi, Fa, Sol, La (taken in their significancy) are necessary assistance to the right Tuning of the Degrees of Sound, as will presently appear. The other two Ut, and Re, are superfluous, and therefore laid aside by most Modern Teachers."

The seven letters Simpson refers to are the seven letters that are assigned as names to the seven musical tones (A through G) within one octave.

In 1674, John Playford wrote his book, An Introduction to the Skill of Musick. He said, "Four syllables are quite sufficient and less burdensome to the practitioner's memory."

Around this same time, migration to America began and immigrants brought with them the practice of using four syllables. Almost all the books that these immigrants had were printed in England, and most were books with psalms or hymns.

Early Colonial America

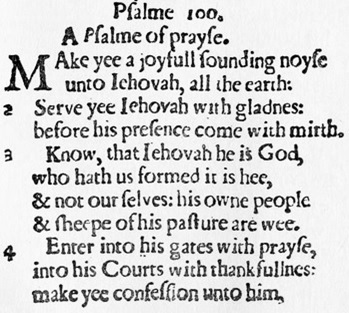

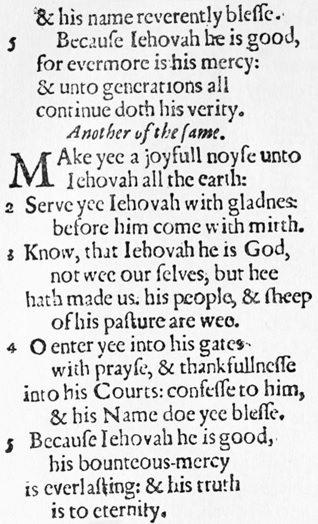

When the Pilgrims settled at Plymouth Rock in 1620, they brought with them the Ainsworth Psalter from Holland. A few years later, the Puritans settled at the Massachusetts Bay Colony bringing with them the Book of Psalms, which was translated into English by Thomas Sternholm and John Hopkins. Both books were printed with words only and without music.

It was not long after their arrival that the Puritans became dissatisfied with their Sternholm and Hopkins' translation of the Psalms, concluding that the compilers had failed to make an accurate translation. In 1640, they published a new psalm book titled The Bay Psalm Book. This book was printed at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and it has the distinction of being the first book to be printed in North America other than Mexico. This book was adopted by both the Puritans and the Pilgrims.

In 1698, the ninth edition of The Bay Psalm Book was published. This edition added 13 musical notations. Under each note there is a notation of "f," "s," "l," or "m" to represent "Fa," "Sol," "La," or "Mi." This edition gives this direction "for ordering the voice setting" for the tunes of the psalms:

"First observe of how many notes' compass the tune is. Next, the place of your first note, and how many notes above and below that, so as you may being the tune of your first note (so that) the rest may be sung in the compass of your and the people's voices, without squeaking above or grumbling below."

The First Tune Books

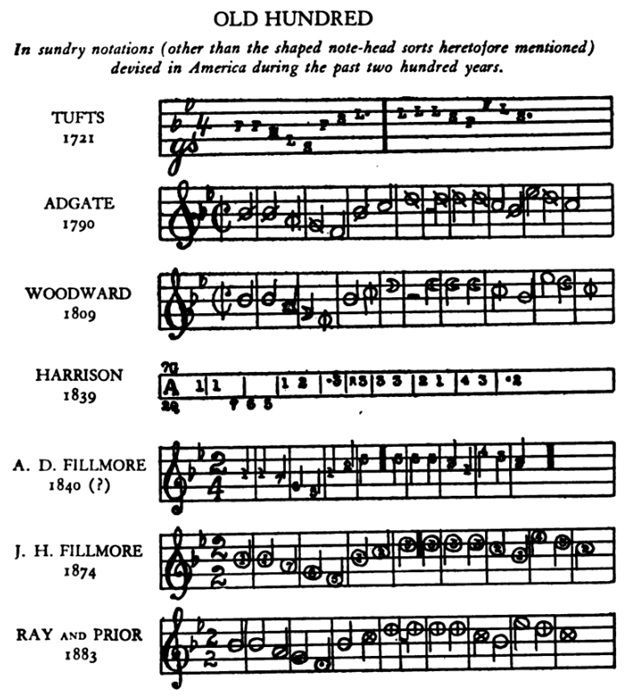

In 1721, the first tune books were published. One was published by Rev. John Tufts of Newbury, Massachusetts, and the other by Rev. Thomas Walter of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Tufts' book was titled An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes in a Plain & Easy Method. He used the letters "F," "S," "L," and "M" (the initials of "Fa," "Sol," "La," and "Mi") on the staff in place of note heads. To distinguish the length of the note, "F" indicated a quarter note, "F." a half note, and "F:" a whole note. He used vertical bar-lines, instead of measure bars, to show the end of musical phrases.

The publication of Tufts' book led to singing schools, and influenced American music education until Lowell Mason began to push music education in a different direction.

Walter's book, The Grounds and Rules of Musick Explained, was significant in the fact that it was the very first American song book to use regular notes of the day. This book was printed on James Franklin's printing press. James' younger brother, Benjamin, was an apprentice in the print shop.

Rev. Thomas Symmes, of Bradford, Massachusetts, was a supporter of Walter's new book. He published a series of pamphlets to promote and support this book. In one pamphlet, he states, "Of all Beasts, there is none that is not delighted with Harmony, but only the Ass."

As time progressed, the popularity of singing schools grew. A singing school teacher would come to a town and teach for two or three weeks. Classes were often held in churches, halls, or taverns. Students were taught clefs, syllables or notes, keys, and note and rest lengths. Students would bring their own candles, and evening sessions lasted about three hours.

Of course, there were some objections to the singing schools. People were kept out past 8:00 p.m., and some claimed that the notes would lead to popery, since the names of the syllables originated in Italy. Some claimed, "If we once begin to sing by note the next thing will be to pray by rule and preach by rule."

Shape-note Tune Books

About 1800, three gentlemen contacted a Philadelphia shopkeeper named John Connelley. Two of them, William Smith and William Little, published a tune book using shape-notes in 1801 titled The Easy Instructor. The third, Andrew Law, published a different tune book using shaped notes in 1803 titled The Art of Singing. More later in their repective sections.

Opposition to Shape-notes

Not everyone welcomed the shape-note system. Individuals such as Lowell Mason, Timothy B. Mason, Thomas Hastings, and William B. Bradbury did all that they could to prevent the advancing of the shape-note system. They referred to shape-notes in a derogatory manner as "buckwheat notes" or "dunce notes." They did promote singing the syllables from round notes. It was their opinion that the better music came from Europe, and not from America; hence, the shape-note singers refer to these gentlemen, and others like them, as "Better Music Boys."

The Better Music Boys were successful in eliminating shape-note usage in the Northern United States. The shape-note singing practice drifted West (now Midwest) and South. Shape-note usage would eventually fade in what is now the Midwest. Despite their efforts, Hastings, Bradbury, and Lowell Mason ironically have several of their own hymn tunes published in shape-note tune books.

Lowell Mason would eventually become known as the Father of American Music Education.

The Hymn Poets

Many of the hymns in these books were written by prolific writers in England, especially Isaac Watts, Philip Doddridge, Charles Wesley, John Newton, and William Cowper. Isaac Watts (1674-1748) was a nonconformist minister, known as the "Father of English Hymnody." In his youth, it was customary to sing from the Psalms during the church worship service. About 1696, Watts complained how dull and lifeless the Psalm singing was. His father, who was the minister of the church, challenged him to write something better.

Watts opened his Bible to Revelation 5 to the story in which the four and twenty elders sung a new song. He wrote a poetic variation of the text. The first stanza of that hymn read:

BEHOLD the Glories of the Lamb

Amidst his Father's Throne:

Prepare new Honours for his Name

And Songs before unknown.

This hymn was sung at the next worship service. The last two lines in the first stanza of Watt's first hymn would be prophetic. As other hymn writers would follow, new praises were "prepared;" and worshipers began singing "songs before unknown." This hymn was so well received that Watts was encouraged to write more hymns. Watts would write over 700 hymns in his lifetime.

Philip Doddridge (1702-1751) was a nonconformist minister. He wrote over 370 hymns during his lifetime. At the time of his death, his hymns were still in manuscript form. In 1755, his friend, Rev. Job Orton, posthumously published Doddridge's hymns.

John Wesley and his brother, Charles (1707-1788) were ministers in the Church of England. They started the Methodism movement, which led to the Methodist Church. Charles' hymns supported that movement; however, even though John advocated a complete separation from the Church of England, Charles refused to acknowledge that separation. Charles wrote over 6,000 hymns.

John Newton (1725-1807) was influenced at a young age by his pious mother, who was a faithful Dissenter. She died when Newton was seven years old. When he was eleven, he went to sea with his father. Newton learned the ways of the sea and grew into a "godless" sailor. However, after reading a book by Thomas à Kempis, Imitation of Christ, Newton began to move toward conversion. One night shortly afterwards, there were complications with the water-logged ship Newton was steering, and, for a moment he faced death. Although he miraculously survived, it took six years while commanding a slave ship for his Christian belief to mature.

Newton eventually went into the ministry, and over time he made his way to Olney. Here he befriended William Cowper. At Olney, Newton published Olney Hymns: in Three Books in 1779. Newton invited Cowper to contribute hymns that he had written. The hymnbook contains 348 hymns: 280 were written by Newton, and 68 were written by Cowper. Newton wrote in his preface that the two chief motives for writing the hymns were "a desire to promote the faith and comfort of sincere Christians, and secondly, to raise a monument to perpetuate the remembrance of an intimate and endeared friendship."

William Cowper (1731-1800) (pronounced "Cooper") was a poet. He translated Homer's Iliad and Odyssey to English. In 1763 he suffered from a deep depression and eventually made three attempts to take his own life-each time, his efforts would fail. After the third attempt at suicide later that year, his family had him committed to St. Albans Insane Asylum. It was at St. Albans when he learned about the love of God. He would later use this experience for his hymn writing.

While living at Olney, Cowper befriended Rev. John Newton. Newton compiled a hymnbook that contained hymns that he wrote, which also included 68 hymns written by Cowper. The book was titled Olney Hymns: in Three Books.

Other hymns used in the shape-note books were taken from different hymnbooks. These hymnbooks were published in America from about 1790 until about 1850. This period of time is also known as the Second Great Awakening. These hymnbooks contain only the texts of the hymn poetry, and there is no musical notation. Many denominations used these hymnbooks before they published hymnals that contained music.

Some of these hymnbooks do give credit to the hymn poet, while some do not. Some credited poetry writers include John Leland, Caleb Jarvis Taylor, George Askins, and John Adam Granade.

The Music

One distinction of this music, at least in the older oblong books, is the open harmony, or dispersed harmony, of the music. Dispersed harmony occurs when a chord exceeds two octaves, or when a lower voice part goes higher than a higher voice part. This would have the opposite effect of close harmony where voice parts are spaced as closely as possible, and the voice parts do not cross. Dispersed harmony also tends to include parallel fifths, octaves, and unisons.

Many of the tunes in the shape-note books were taken from folk songs, ballads, and drinking songs. Arrangers added harmonies and hymn poetry to the tunes.

The Composers

In the mid-1700s music books were published in England by such composers as William Tans'ur, Aaron Williams, William Knapp, Joseph Arnold, and John Stephenson. Their music was "set, or harmonized, in the most-simple manner; containing principally the common chords, without any regard to the modern rules of relation and progression." Their publications appeared in Great Britain and eventually in Colonial America.

In New England, William Billings may have been influenced by the works of these composers. Billings wrote in the introduction of his book, New England Psalm-Singer, "I don't think myself confin'd [sic] to any Rules for Composition laid down by any that went before me." It appears from this statement that Billings was self-taught musically, and it may be that he self-studied from the works of these gentlemen from England.

There were other composers in New England during the Colonial and Revolutionary period. Like Billings, most were either self-taught or influenced by other singers of this tradition. These American composers, unlike European composers, such as Bach or Beethoven, were not able to make their living from music. Billings was a tanner. Justin Morgan owned a tavern and was a horse breeder. Francis Hopkinson was a lawyer and a politician; he was also a signer of The Declaration of Independence.

In the 1800s and 1900s, compilers of various tune books were also composers. B. F. White 1 (the "Author of The Sacred Harp") and William Walker 2 (the "Author of The Southern Harmony" and The Christian Harmony) probably composed most of the tunes. As other tunes books were compiled or revised, other individuals submitted their own compositions for the new books. Some of these composers include Edmond Dumas, Absolom Ogletree, John Palmer Rees, Henry Smith Rees, and William Bobo.

There are a few tunes by European composers including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Arne, and Ignaz Josef Pleyel. William Walker also included in The Christian Harmony a few songs credited to George Frederick Handel, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Franz Joseph Haydn. Many were small portions of much larger works--as is the case with most of the European tunes in the books. The Christian Harmony also has one song composed by Martin Luther and one by John Huss; both were church reformers during the Protestant Reformation era.

Despite his opposition to the use of shape-notes and dispersed harmony, hymn tunes that were composed by Lowell Mason, one of the "Better Music Boys," were included in several of the Shape-Note books. Mason's hymn tune of "Hamburg," commonly used for "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross," can be found in many shape-note books. A couple examples of hymns that were composed by William Bradbury include "Angel Band" and "The Solid Rock." "Rock of Ages," composed by Thomas Hastings can often be found in some of these tune books.

There are not many pieces where the composer of the hymn tune also wrote the hymn poetry. Many of these tunes were composed and written in the 1900s. The 1991 Denson Edition of The Sacred Harp contains several songs whose tunes and poetry were both written by the same person. For example, Owen W. Denson wrote "Lord, We Adore Thee." John T. Hocutt wrote "Redemption" and "The Resurrection Day." In the Cooper Edition of The Sacred Harp has a song written and composed by Benjamin L. Vaughn, "A Golden Crown to Wear." John W. Miller wrote "Shades of Night" and "My Home Above." There are some songs in the Denson and Cooper Editions of The Sacred Harp and the 2010 Edition of The Christian Harmony with hymns and their lyrics by O. A. Parris.

In the mid-1800s when these books were first published, there are some hymn tunes where the hymn writer was not credited. In these cases, it was the first time the music and the poetry were published. It cannot be proven now, but it is possible that both the music and the poetry were written by the same individual.

One song of interest is "Portuguese Hymn." It was composed in 1743 by John Francis Wade who also wrote the hymn poem in Latin as Adeste Fideles. The English translation that we use in our books was translated by Benjamin Carr in 1805. The more familiar English words of "O Come, All Ye Faithful" was translated in 1841 by Frederick Oakley.

Shape-Note Singing Today

In spite of the efforts of the Better Music Boys, shape-note singing is still a robust activity. The singings today are going strong in most places. There are some singing places where the singings have dwindled either a low attendamce, or even ceased to exist. Attencence has either dropped, or a certain supporter has passed away. Sometimes, the rent to using a local facility has bumped higher than what a local group could afford to pay.

Fortunately, there are new singings that now exist in places outside of the south--not only within the United States, but there are a few in other countries throughout the world.

There are some books in these write ups that are have discontinued. There are some books in these write ups that were not included--some are still in use, and some have been discontinued. The influence from these old books continues to live. There are songs in discontinued books that were later published in other books. The same is also true for some of the books that are still in print--they, too, have songs that were printed in other books.

Sources:

American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Volume 28. (Philadelphia: American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, 1917).

Appel, Richard G. The Music of the Bay Psalm Book: 9th Ed. (1698). (Brooklyn: Institute for Studies in American Music, Department of Music, School of Performing Arts, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, 1969.)

"William Cowper (1731-1800)". Cowper & Newton Museum (19 August 2017).

"John Newton (1725-1807)". . Cowper & Newton Museum (19 August 2017).

Eames, Wilberforce. The Bay Psalm Book: Being a Facsimile Reprint of the First Edition, Printed by Stephen Daye at Cambridge, in New England in 1640. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1903).

Fedele, Gene. Heroes of the Faith. (Gainsville, FL: Bridge-Logos, 2003).

"Guido of Arezzo." Catholic Encyclopedia (Catholic Online, 1907-1912), <http://www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=5444> (3 March 2017).

Jackson, George Pullen. White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933).

Julian, John. A Dictionary of Hymnology, Setting Forth the Origin and History of Christian Hymns of All Ages and Nations. (London: John Murray, 1892).

McLemore, B. F. Tracing the Roots of Southern Gospel Singers. (Jasper, TX: B. F. (Bob) McLemore, 2005).

McNaught, W. G. "The History and Uses of the Sol-Fa Syllables" Proceedings of the Musical Association for the Investigation and Discussion of Subjects Connected with the Art and Science of Music, Volume 19, 1892-93. (London: Novello, Ewer and Co., 1893).

Moore, John Weeks. Complete encyclopaedia of music: elementary, technical, historical, biographical, vocal, and instrumental. (Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co, 1875).

Morley, Thomas. A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke Set Downe in Forme of a Dialogue: Divided Into Three Parts. The first teacheth to sing, with all things necessarie for the knowledge of pricktsong. The second treateth of descante, and to sing two parts in one upon a plainsong or ground, with other things necessarie for a descanter. The third and last part entreateth of composition of three, foure, five or more parts, with many profitable rules to that effect. With new songs of, 2. 3. 4. and 5. Parts. (London: Humfrey Lownes, 1608).

Playford, John. An Introduction to the Skill of Musick (London: Printed by W. Godbid, 1674).

"Reverend Philip Doddridge." (Kibworth History Society), <http://www.kibworth.org/doddridge.html> (19 August 2017).

Simpson, Christopher. A Compendium: or, Introduction to Practical Music in Five Parts. Eighth Edition. (London: Printed by W. Pearson, 1732).

Tawa, Nicholas E. From Psalm to Symphony: A History of Music in New England. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001).

"Thomas à Kempis." Catholic Encyclopedia. (New Advent). <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14661a.htm> (19 August 2017).

Watts, Isaac. Hymns and Spiritual Songs: In Three Books. 1773 ed. (London: S. Strahan et. al., 1773).

Wright, Thomas. The Life of William Cowper. (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1892).

Vaughn, R. L. Songs before Unknown: A Companion to The Sacred Harp Revised Cooper Edition 2012. (Mount Enterprise, TX: Waymark Publications, 2015).

1 In the 1860 U. S. census record for Harris County, Georgia, lists B. F. White's occupation as "Author of Sacred Harp." B. F. White household, 1860 U. S. census, Harris County, Georgia, population schedule, Georgia Military District 672, Hamilton post office, page 36, dwelling 247, family 247, National Archives microfilm publication M653, roll 126.

2 The name on William Walker's gravestone is listed as "W. Walker A.S.H." He is buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Spartanburg, Spartanburg County, South Carolina. Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com: accessed 17 December 2017), memorial page for William "Singing Billy" Walker (6 May 1809-24 Sep 1875), Find A Grave Memorial no. 32607297, citing Magnolia Cemetery, Spartanburg, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, USA; Maintained by Find A Grave.